Reading the back (way back) issues of The Brill Report has brought on the flashbacks big-time. Many of the bit players whose names (and cards) had escaped me over the last 20 years have come charging back like William Perry astride a donkey.

There’s the Ted Williams Card Company, a high-concept piece of sports-marketing detritus that was a better idea than the Sandy Consegura Card Company, but only marginally. (We shall write about the TWCC at greater length when we clean out the vacuum-cleaner bag.)

There are the Assets phone cards from Classic and Kayo’s America’s Cup set, part of Kayo’s grand scheme to corner the market on crappy licenses for quasi-sports. After all, nothing says “misguided” like a 24-karat-gold card of Dennis Conner.

And then there’s Wild Card. I had forgotten about Wild Card for several reasons, but mainly because its product was so godawful in concept and execution.

Okay, so the very basic, basic concept behind Wild Card wasn’t godawful. It was even a wee bit inspired, in a self-referential sort of way.

Start with the name: Wild Card. Roughly defined, a wild card is something of value – interest, at least – that appears on an unexpected basis. How much of the Handful O’Landfill era was built around that conceit? The more you buy, the higher up the theoretical ladder you can climb. Buy enough – and we mean enough enough – and you can get a genuine authentic jersey-fragment card of Browning Nagle.[1]

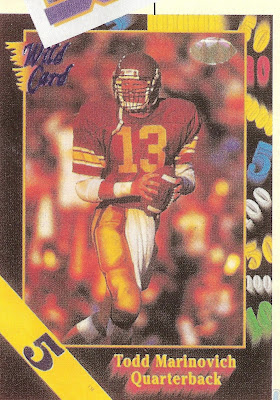

With Wild Card, that conceit even extended into the base set. Each Wild Card card (is that right?) had a point value printed on the front. Most were one-point cards[2]. There were proportionally fewer five-, 10-, 25-, 50-, and 100-point cards, and far fewer 1,000-point cards. You could, if you had a masochistic streak as wide as the Monongahela, collect 100 one-point cards of Amp Lee or some other schlubby NFL draft pick and trade them for a 100-point card. Collect enough point cards of a given player and you could trade them in for an autograph or something similar, though not anything useful, like a washer-dryer. It was like Let’s Make A Deal with the base set as the zonks.

Again, Wild Card, not a terrible idea for a card set. Certainly worse ideas have been allowed onto the market. (We’re talking to you, Pinnacle Inside.) The problem with Wild Card was that the execution was exactly that. Wild Card took this idea out back, blindfolded it, offered it a cigarette, and blasted it to smithereens with some antediluvian fowling piece lifted off of Sons of Guns: Winnemucca.

The logo was ripped – flames, ragged edge, and all – out of a third-grader’s social-studies notebook. The pictures were taken at night with a cell phone, a feat made only slightly less remarkable by the fact that the cell-phone camera hadn’t been invented yet. The backs were written in Twitter on a Magnadoodle by Johnny Manziel. The remaining graphics were designed, if you want to call it that, by people who view a glittery puffy sticker of a goldfish as the pinnacle of modern art.

In a trading-card world full of Star Pics cards of Really Obscure Draft Picks Taken From a Long, Long Ways Away and Traks racing cards of tire-changers reading newspapers, this was the nadir. If you took the world’s worst tattoo artist, gave them a Barbie Fabulous Fuzzy Digital Camera and a nail, and told them to create a card set, they would have come up with something better than Wild Card.

Here’s another reason I had forgotten Wild Card: Wild Card’s card-producing lifespan ran from mid-1991 to late 1992, with a quick breather in mid-1992. I got engaged in 1991 and married in '92, and why would I want to sully two otherwise perfectly wonderful years with memories of some perfectly awful trading-card sets?

Speaking of awful, Wild Card’s coup was landing the license for the World League of American Football, the League Subsequently (And Oh-So-Misleadingly) Known As NFL Europe, the league with the most spot-on acronym in pro sports (WLAF, with the accent on the “laf”), the league that bedecked the fabled capitals of western civilization with teams full of CFL rejects named Amir Rasul, Mike Prugle, Ron Sancho, Cornell Burbage, and Joe Howard-Johnson, the league that out of nearly a decade of grinding effort and vein-popping concentration gave the NFL … Stan Gelbaugh.

It’s a reasonable match. If you want it bad enough you can have a Wild Card WLAF card of Falanda Newton. But I don’t know anyone who wants that bad enough.

About that sheriff’s sale: In late 1994, and without explanation for how Wild Card spent 1993 and most of ’94[3], a sheriff’s sale was held in Cincinnati to dispose of Wild Card’s assets. I can’t imagine what was in the sale – I’m guessing thousands of cards of Will Furrer, Tommy Maddox, Siran Stacy, Darryl Williams, Tommy Vardell, Quentin Coryatt, Ty Detmer, and David Klingler, with a couple of Babe Laufenberg autos as lagniappe – and how anyone could call them “assets” with a straight face, but Bob Brill pulled it off. At least, there weren’t phlegm stains on my Brill Report from Bob coughing up a lung in laughter.

It’s a very real possibility that they held the sheriff’s sale and no one came, meaning that if you ever get arrested in the Cincinnati area, while they’re slapping the cuffs on you and the officer reaches into his pocket and pulls out a card, instead of, “You have the right to remain silent,” you may hear, “Former Packers signal-caller Anthony Dilweg is hoping for big things at the helm of the Montreal Machine.”

At that point you may just want to plead guilty and be done with it.

[1] Or this year’s Browning Nagle, Geno Smith.

[2] I’m doing this from memory, so I may mess up some of the details. But take my word for it: It really doesn’t matter.

[3] Beating the bushes for the next WLAF is a possibility.